Mongolia, Multimedia Memories, and Me.

by Joe Buchman 2013 (restored 2023 from archive.org by Jacob)

I first experienced just how much the Internet had changed my life late one afternoon, in an Internet cafe in downtown Ulaanbaatar. Ulaanbaatar, the modern-day capital of the newly independent nation of Mongolia, today represents what must be the height of Soviet infrastructure and architectural design in decline. It’s a city abandoned a decade ago by its foreign central planners. After 70 years of Soviet domination, they left behind a crumbling communist substitute for what had been the ancient Mongol capitol of Karakorum. From the walled Xanadu of Karakorum the Great Khans had once entertained artisans and emissaries from across Asia and Europe as they ruled the largest nation-state ever seen on earth.

Once Upon a Time . . .

It was the Mongol Conquest begun by Chinggis Khan almost 800 years ago that brought Europe out of the slumber of its Dark Ages and first opened the world to free trade, safe travel, and an unprecedented international exchange of information. Some cite the Mongol Conquest as the most significant single event in human history due to its expansion of international communication about science, politics, medicine, and astronomy. From Vietnam to Vienna (or Syria to Siberia, depending on your preferred alliteration), Chinggis Khan, his sons and grandsons, conquered, killed, and ultimately transformed the world in ways that ripple out from that time to affect our lives even today. For example, without the Mongol Conquest, Columbus would not have sought out a shorter trade route to the riches of the East, and the European “discovery” of America would probably not have occurred for another hundred years or more. The Mongol Conquest was a foreshadowing of the kind of transnational sharing of information that wouldn’t occur again until the development of the first electronic media. Yet Mongolia itself would be one of the last places on earth to experience its impact. It wasn’t until 1967 that the first television broadcasts originated in Ulaanbaatar, and for most of the past century, Mongolia itself was closed to outsiders to protect the secrecy of its Soviet military bases.

Following the collapse of the U.S.S.R. in 1991, those bases were dismantled and abandoned. Two hours south of Ulaanbaatar, near the northern edge of the Gobi desert, the longest runway in Mongolia lies abandoned near the small town of Choir. From here the Soviets targeted Los Angeles and San Francisco with intercontinental nuclear missiles, yet today Choir and its abandoned military base have been declared a free enterprise zone. I marvel at the idea of that, sitting in the Internet cafe, looking out its picture window across the parking lot, to a giant stone Lenin, standing with his back toward me. While the Mongols suffered under communist domination—and even though 30,000 to 50,000 Buddhist lamas were murdered in the Stalinist purges of the 1930s — Mongolians today still express profound gratitude to the Soviets for at least keeping China from taking all of Mongolia in the 1920s.

Anna Buchman with a friend in Khovd, in the far western Altai Mountains of Mongolia.

For the past 20 years, as a university professor of telecommunications and multimedia management, I’ve been lecturing on how the convergence of electronic media has “revolutionized the world.” How a new bloodless conquest, even greater than that of the Mongols, would again break geographic and political barriers, shoot ideas around the globe at unprecedented speed, and gather like-minded passionate individuals into virtual communities based on their shared values rather than shared geography. Still, there was a moment in that Internet cafe for which no lecture could have prepared me either as a student or as the sage-on-the-stage delivering it. It’s one thing to talk about how the Internet can change life, it’s another to experience it firsthand.

Beam Me Up, Scottie

This particular Internet cafe, one of dozens in Ulaanbaatar, is an island of high-tech free enterprise tucked into the display-windowed front corner of what had once been the gilded headquarters building of, of all things, the Communist Party of Mongolia. Across the marbled hall in the opposite corner of the building, clerks are ringing up sales of duty-free Chinggis Khan Vodka by the liter and selling tickets to and paper for the Western-style toilets upstairs. While the inside of the Internet cafe resembles, in both its circular layout and furnishings, the bridge of the Starship Enterprise, outside the window lies a scene as alien as any Captains Archer, Kirk, or Picard ever saw.

The author at the “Enterprise” Internet cafe in Ulaanbaatar.

Ulaanbaatar today is a unique mix of crumbling old technologies and infrastructure with vibrant new ones floating around on top. The younger generation, those under 30, who came of age after the Soviets left, must look almost like the Borg to their parents and nomadic grandparents. The Panasonic store three blocks west of my starship Internet cafe sells a bewildering array of DVD players, mini-DV camcorders, video projectors, and home theater accessories. It’s what might have been the result if some Star Trek script had the Enterprise drop in on a basically preindustrial, nomadic planet and accidentally leave behind a cargo hold of cell phones, computers, and digital video equipment. (Now that I think about it, wasn’t this exactly the plot for two Star Trek episodes, one with Nazis and the other with 1930s-era Chicagoland gangsters?)

I’m fairly certain the wired telephone exchange in Ulaanbaatar has never fully worked, but cell phones were in one or both hands of every Mongolian adult under the age of 25 whom we met. The plumbing, electricity, hot water, bridges are all crumbling, or creak along sending the city into blackouts, gridlock, and foul flooding; while technologies of this century—cell phones and state-of-the-art, high-speed Internet cafes—reside on almost every street corner. Several French friends told us that Ulaanbaatar has more Internet cafes than Paris, and I believe it. In Paris, a home PC or laptop can be fearlessly connected to the wired phone system. Here it is a life-threatening adventure. In Ulaanbaatar the phones can’t be relied upon to reach your neighbor, much less a noise-free connection to a modem at a voltage that won’t fry the insides of your PC. Most email and Internet surfing occurs away from home, for the equivalent of about a dollar an hour, with occasional “corner gas station”-like price wars among the free-market Mongolian Internet entrepreneurs dropping prices even below that.

A Mongolian shaman in his home, with the author’s son, Kristian.

But the moment I realized the world had truly changed for me was when I got the confirmation that the lease had been signed. You see, from that Internet cafe in Ulaanbaatar, over the course of less than a week, I had successfully met, negotiated with, and rented our home in Alpine, Utah, to a couple from New Jersey, 12 times zones away — all via email from the front room of what had once been the former Communist Party Headquarters. I wondered who would have been more surprised: Lenin, whose statued backside looked down on it all from the park across the street; Chinggis Khan, who first, as a side effect of his campaigns, opened so much of the world to travel and free trade; or me? In spite of all those lectures about “bringing the world closer together,” I still expect it was me.

The American Invasion

A year later, we returned to Mongolia, this time with our four children in tow. I guess we must be the only foreigners to take a two-year-old American to Khovd, in the far western Altai Mountains of Mongolia, for Naadam, the national holiday. I suspect this because, upon our return from Khovd to Ulaanbaatar, Mongolian State Television showed up at our friend’s apartment in Ulaanbaatar to interview us. They wanted to know if this meant all Americans were ready to experience Mongolian tourism and what our friends in America thought of Naadam.

We spent about a month with Anna (2) and her sisters Kelsey (12) and Hayley (9) and their brother Kristian (6) living with nomads as far from Ulaanbaatar as we could get. We drank Airag, the Mongolian national drink made from fermented mare’s milk, ate boiled sheep organs, and sang countless folk songs with our Mongolian hosts and friends. I brought along an IBM Thinkpad and Sony mini-DV videocamera (TRV900) with a couple of solar panels that could keep spare batteries for each charged.

The author and his wife, Cindy, with son, Kristian, along with Mormon missionaries and Mongolian friends in front of a ger (or yurt), in Khovd.

Anna, just shy of turning three, loved her time in Mongolia and still remembers much of the trip. Her greatest joy, just after having been potty trained before we left Indiana, was the discovery that in the nomadic countryside she could pee and poop right on the ground, more or less anywhere she felt like it, but usually only after walking a mile or more to find some parched high-steppe desert flower to “water.” I’m not sure my wife, Cindy, has yet forgiven me for answering Anna’s earlier innocent question about where Daddy was going with, “Out to water the flowers.”

The kids learned something that all the electronic distractions of America crowd out from being able to be taught here—the joy of playing together. After a day or two of boredom (clinical withdrawal, I think, from video games, television, telephones, and computer games), all the plug-in drugs of our life in the United States were unplugged and a simple deck of cards, splash in the creek, or learning a folk song took on a new fascination. They got very good at hearts and learned how to “shoot-the-moon” (which resulted in more cries of delight and triumph than I ever heard from any interaction with the Disney Channel, a PC game, or Nintendo) and mastered some Mongolian card games that I still don’t fully understand. They also picked up a fair portion of Mongolian, and now have their own secret way of communicating with each other, which neither Cindy nor I, nor any of our Mongolian friends, can understand.

But the greatest joy of all was riding a Mongolian horse. There’s something special about the bond between a child and a horse. It’s instant, magical, undeniable, and overwhelming. There’s nothing Nintendo or Sony or Microsoft can ever design, I think, to compete with a kid on a horse heading out over the endless steppes. I’ve never witnessed such unbridled joy on another human face as I did on the faces of countless Mongolian children, some as young as three — or on the faces of ours while riding. It’s said that Mongolian children still learn to ride before they learn to walk, and I don’t doubt it for a moment.

Let the Games Begin

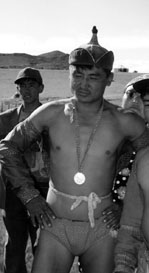

The national holiday, held every year in mid July, is called Naadam. It’s a kind of annual mini-Olympics with only three sports: archery, wrestling, and horseback racing — the three skills that empowered Chinggis Khan’s armies to roll over the best armies in the known world. Wrestling is a men-only competition with skimpy briefs and chest-free jackets to prove no women have snuck in. The wrestlers imitate birds while dancing to songs sung by their coaches and judges before attempting to knock each other to the ground. Dozens of two-person matches occur simultaneously on the infield of a large stadium in Ulaanbaatar and in smaller fields all over the country. The Ulaanbaatar matches are televised; the entire nation stops to watch, keep score, and relate the personal histories of the star wrestlers.

Winner of the wrestling match in Khovd.

Archery is a sport in which both adult men and women may compete, aiming at targets that are a series of cans set on the ground. Surely the most interesting job in Mongolia must be that of the aim-criers, judges who stand next to or right behind the targets, moving out of the way just as the arrow arrives, and singing out the score so as to be heard at the far end of the range.

But horse racing belongs to the children, both boys and girls. Every jockey is between the ages of 4 and 12, with most around 8 or 9 years old. The

Ulaanbaatar races are broadcast as well, with cameramen hanging from madly driven Russian jeeps darting in and out among hundreds of horses and their young riders. The races are cross-country, cover dozens of kilometers, and are broadcast in full.

In Khovd for Naadam last year, one of the judges noticed my Sony TRV900 and asked very politely if I would mind standing right at the finish line for one of the races so if there was a tie, my video could be used to determine the photo-finish. I had worked free-lance for ESPN for the Kentucky Derby in the mid 1980s, but nothing there prepared me for 20 or so Mongolian horses headed straight at me with exhausted eight-year-old jockeys singing loudly and whipping them madly. I think for a moment I knew what the Eastern Europeans must have felt when the Golden Horde came galloping down on them. It’s like a dusty, song-filled earthquake, but I got the shot.

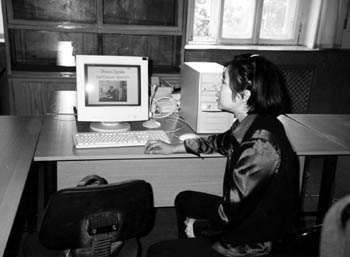

Afterward we went looking for the one Internet connection we had heard was available in Khovd. Two Mormon missionaries (the most permeating elements of Western Culture seem to be Mormons, Snickers bars, and Orange Fanta soda) directed us to the local telephone office. There we learned that the Internet connection had been broken for more than a year and no one appeared to know why or whom they should report it to.

So I decided to pay for a phone call home instead.

After waiting in line at the counter, I filled out a card with my dad’s phone number in the United States, paid $10 in advance, and sat in the waiting room for about an hour with a dozen or so Mongolians, waiting for a phone in one of the three phone booths in all of Khovd to become available. I gather a Mongolian operator, speaking no English, had managed to make a connection with my dad in Indiana. He screens all his calls, but fortunately picked up after he heard some odd language coming out of the answering machine in his kitchen and waited long enough for the operator to buzz me in the phone booth. From 12 time zones and half a world away, we made a connection, and it seemed like a miracle. By now I’d grown accustomed to sending an email from Ulaanbaatar and having a reply from friends in the U.S. in under five minutes, but here a phone call felt like the new unproven technology. At any second I expected to be disconnected, the static, cross-talk, and low hum on the line left me clear that we were truly pushing the edge of what technology could create! For those 10 minutes, the world didn’t seem so small and close after all. My dad, however, couldn’t get over the idea that the phone had buzzed. In almost 80 years he had never heard a phone do anything but ring, and most of my $10 was spent listening to him marvel about that buzzing noise, while I tried to share the potency of mare’s milk, Naadam, and new joys his four grandchildren had found here.

The only Internet connection at a small business college in Ulaanbaatar.

Home Is Where the Flowers Are

Our kids have returned to the public schools of Indiana for a more (by contemporary Western standards at least) “traditional” style of education, but the learning they experienced in Mongolia has remained with them, and with us. Nintendo, computer games, and the latest DVDs still rivet our attention from time to time, but something is different. There’s more hearts, and wrestling, and board games. We carry with us a longing for that month spent living a simple life, surrounded by the loving kindness and curiosity of those gentle, cheerful, generous nomadic people. I think it’s not the result of some advanced, abstract philosophy or religion that gives Mongolians their reputation for almost mythic generosity — it is Nature Herself.

In the harsh environment of the Siberian winter, nomads who don’t give all they have to each other unreservedly, die. Perhaps it’s survival of the fittest, where those who are most fit for that environment are those who are the most kind to each other. Whatever it is, the feeling of being so welcomed by human beings who have so little, seemingly, to share, yet share it all, is healing in ways for which we didn’t even realize we were ill. Without any of our multimedia mechanisms, our Mongolian hosts and new friends feel more real, more authentic, more loving, more full of songs and joy and the simple things that have been said to set men free. Our “more advanced culture,” our technical marvels and electronic distractions, make it so easy to forget the miracles we felt there. But when it seems it’s all about to slip over the horizon of our memories, we just let Anna run into the backyard to water a flower, and it all comes rushing back, even if we can’t quite explain it to our neighbors.